Inspection of the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service West Service Delivery Area

Related Downloads

Summary of findings - Response

How effective is the Service in the WSDA at responding to incidents when they do occur?

61. An effective Fire and Rescue Service will, when the public calls for help, ensure its firefighters respond promptly and possess the right skills, knowledge and equipment to deal with the incident effectively. The Scottish Fire and Rescue Service’s overall effectiveness within the WSDA is judged to be Satisfactory.

Staffing

62. The ability to promptly respond is dependent on the availability of a crew to do so. This is usually directly related to the crewing model at the station closest to the incident. Within the WSDA there are three basic crewing models, Wholetime (WT) and On-Call (which is new nomenclature for the Retained Duty System (RDS) and Volunteer Duty Systems (VDS)). WT stations are crewed by fulltime firefighters working a five watch duty system 5WDS. On-Call stations work on an ‘as required’ basis, where personnel respond to a pager alert and attend the station when requested, this therefore builds in a delay before the appliance can leave the station.

63. A fire station’s establishment is based on the Service’s crewing level policy. In practice there are occasionally times when there are more than the required personnel on duty and other times where there are not enough. For WT, the SFRS 5WDS is based on a 10-week, continually repeating, shift cycle. The 5WDS is designed to predict as far as practicable, where surpluses and deficiencies will occur, and realign resources accordingly. To ensure the duty system and WT firefighter availability operates efficiently the Service has a national Central Staffing (CS) department. CS is responsible for arranging the number of operational personnel on duty at each Wholetime fire station. This is done by the management of leave, use of overtime, the use of the additional out of pattern roster reserve days (orange days) and the use of detached duty staff.

64. To assist the CS team and manage absence the Service also employs an appliance withdrawal strategy. Staff reported that due to the shortage of personnel there have been daily withdrawal of appliances in some areas in the WSDA, normally the second pump at an affected station. When this happens, the crew from that appliance will then be detached to make up the numbers at other stations. Due to the specialist rescue capabilities, and crewing requirements of some stations, those stations don’t normally form part of the withdrawal strategy and are broadly unaffected. This however places an added burden on other surrounding stations. Prior to the COVID pandemic, appliances in stations with two pumps were crewed to a minimum of five firefighters on the first appliance and four on the second and at one pump stations with a minimum of five firefighters. In response to the pandemic, crewing was reduced to a minimum of four on all appliances and this remained the standard for that period and beyond.

65. Service provided statistics demonstrated staffing levels at 93% FTE of the TOM year ending the 31 March 2023, equating to a deficit of about 100 firefighters. We found that this reduced crewing level frustrated operational firefighters as it could lead to increased detached duties, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) transport issues, consistent and regular appliance withdrawal, overtime fatigue, difficulty in getting time off in lieu etc. That said, latterly in our fieldwork, due to the operational changes brought about by SSRP, HRA Strategy and the rationalisation of Water Rescue in September 2023 we found that WT operational crews were generally established to or around the TOM. Although there were still instances of appliance withdrawal and appliances being staffed to four, we found that the picture had in the main improved and there was reduced negative feedback regarding this particular issue.

66. As detailed, Detached Duty (DD) involves personnel temporarily working from a fire station other than their home station to make up a crewing shortfall. The Service has reported that following the modernisation changes in September 2023, there has been an overall decrease in DDs across the WSDA and Scotland as a whole. However, staff reported that in some locations DD had increased following the September changes and that this may be mainly caused by the displacement of staff and consequently local skills shortages in fire appliance driving and specialisms. Frustration and concerns raised by staff, were the disruption to organised training and completion of SVQ development with their own watch and station, restricted ability to get time off as well as general welfare issues surrounding the constant additional travel and impact on home life. In addition, there were many instances of Watches only having one or two appliance drivers and the same person constantly driving a fire appliance, thus reducing their opportunity to carry out other tasks. We were told of instances of individual drivers spending long periods of time, without regularly running in the position as a Breathing Apparatus (BA) Operator. The limitations of skills also exacerbated the fact that Drivers and Specialists find it very difficult to get time off in lieu and that this group of employees would seem to be disproportionately affected.

Recommendation 5: We recommend that the Service review its Fire Appliance Driver and Specialist capacity in the WSDA to understand the areas of most pressure and apply mitigation, which allows firefighters to practice variety in the role on a more regular basis.

67. For On-Call staffing levels, the SFRS normally has a TOM of between 10 to 20 firefighters (or 1000% to 2000%) depending on the size of the station, the number of appliance and any specialism etc. The percentage system allows management to employ more people on a reduced contract, thus more people, with the expectation that this will increase availability. Service provided statistic demonstrated staffing levels of between 67% and 83% for RDS and 66% and 70% for VDS, depending on the LSO area. An outlier to these figures was the low staffing levels (29%) at Leadhills Fire Station in South Lanarkshire, which was ultimately subject to closure following a public consultation process. The staffing levels, which are far from ideal, are indicative of the ongoing issues that the UK Fire Service has with recruitment and retention in the On-Call duty systems, which will be dealt with later in the report. In the WSDA, the Service has increased the use of Dual Contracts by 11% from 2022 to 2023 and this efficient and effective use of existing firefighters should be commended.

Availability

68. The Service monitors the availability of On-Call appliances electronically. Like other areas across Scotland and the wider UK there are occasions, particularly during the day, when an On-Call appliance may not be available. Once the number of personnel available falls below the minimum number, with the correct skill set required to crew an appliance, it will be deemed unavailable and would automatically not be mobilised to an incident. In these circumstances the next nearest available appliance would be mobilised. Availability is usually higher during the night and at weekends. There are a number of factors which influence On-Call availability and the trend in recent years of people no longer working within their local communities continues to impact on personnel’s ability to respond, particularly during the day.

69. The total average On-Call availability within the WSDA was just over 77% for the year ending 31 March 2023 with one LSO area averaging a low of 67% and one LSO area averaging a high of 86%. Outside of the average availability there were examples of some appliances having very poor availability on a routine basis. There could be many factors for these differences such as demographic, geography, industry, commerce, etc. and each area has unique issues and as such, comparison is difficult. We found recruitment and retention and consequential reduced appliance availability to be a continued area of challenge for the WSDA, which is discussed in more detail later in the report.

70. We also noted that poor availability had an inevitable impact on Wholetime appliances and staff. We were provided with numerous examples of WT appliance routinely travel large distances to cover ‘cluster’ areas and to provide availability in a remote rural location for a period of time, normally through a day shift. The impact on these WT personnel was significant with reduced fire cover in urban areas, lost training time, inefficient use of fuel and resources, lost operational preparedness capacity and increased road risk management as examples given. Additionally, staff raised concern that some On-Call staff within the WSDA were still on different contracts with different expectations of availability depending on the legacy Fire and Rescue Service (FRS) area. This was a source of frustration and there was a sense of unfairness, given the period of time passed since the inception of the new Service.

71. On-Call personnel use a system called Gartan to individually manage their own availability. At several On-Call fire stations personnel will also informally and collectively manage their personal availability, to ensure that an appliance will remain available. An example, used at numerous stations, included running a two watch system, which allowed scheduled time off for personal issues whilst still guaranteeing appliance availability. Other WSDA availability solutions included the use of 50% dual staffing contracts for Wholetime personnel, use of a bank hour system and employing the On-Call support Watch Commander (WC) to fill any foreseeable gaps. Staff observed that these systems were effective to a degree but were not sufficient to attract and retain personnel in some rural areas.

Good Practice 3: We were very pleased to observe proactive management of On-Call Availability and examples of innovative local staffing solutions, such as the increased use of dual staffing, which made the system more user friendly.

72. We did note that each LSO management team was continually monitoring the availability levels and were working hard, within the constraints of Finance and Conditions of Service, with the local crews to maintain and improve availability using innovative solutions. Unfortunately, on occasions, this monitoring was perceived as being overbearing and punitive with crews resenting the subsequent management. It should be noted that there are many stations in the WSDA where the availability of appliances is very good and the personnel at these stations should be commended for maintaining these high standards.

Community Fire Stations

73. The Service introduced an Asset Management Policy 23-28 in February 2024. The policy aims to support every member of the workforce by ensuring they have the right equipment, fleet and property assets to do their job to the best of their ability. There has been significant progress in developing this strategic approach with work undertaken on the creation of Strategic Asset Management Plans for equipment, fleet and property. The Service published the Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMPP): Property 23-28(3), which sets out how the SFRS aims to achieve a modern and fit for purpose property estate that supports the effective delivery of services across the whole organisation. The Strategy details many identified issues with Fire Stations throughout Scotland and highlights many as not having minimum toilet facilities, dedicated drying facilities, rest or canteen facilities, dedicated locker rooms, sufficient showering facilities, dedicated water supply, dignified facilities and appropriate contaminant control measures.

Good Practice 4: We were pleased to observe the development of the Asset Management Policy and SAMPs as they provide clearer direction with regards to future asset investment, development and review requirements.

74. The Service has also had a Property Condition Survey carried out on each fire station in the WSDA from approximately 2019 to 2023. The surveys give SFRS’s managers information regarding the assessed condition of the fabric and services of the building, and to a degree, indicative costs for any identified refurbishment. A Corporate Landlord model details each station’s rating regarding condition and suitability. With regards to condition, out of 127 Fire Stations, the WSDA had 44% in satisfactory condition, 54% in poor condition and 2% in bad condition. With regard to suitability, 17% were good, 21% were satisfactory, 46% were poor and 16% were bad. This information generally allows local property managers to prioritise improvement work. However, Capital and Revenue expenditure priorities on premises refurbishment and repair is a national matter, in consultation with LSO area staff.

75. Our feedback from staff regarding their workplace generally resonated with the SAMPP assessments and issues of concern. Specifically, staff reported concerns regarding lack of dignified facilities, drying facilities, PPE storage areas, appliance exhaust ventilation, BA Set servicing areas and difficulty in controlling and eliminating exposure to contaminants. In addition, we also found concerns surrounding training towers being out of use due to pest contamination, poor broadband connectivity and limited computer provision. We also found that many staff, especially in remote rural stations, were extremely frustrated by the limited provision of local BA cylinder recharging facilities. In many cases it was reported that this caused unnecessary appliance movements, difficulty in transporting spare cylinders and that the protection of the cylinder resource sometimes caused a reluctance to properly train in BA.

76. Many of the issues observed in the previous paragraph were supported by our Survey. We posed the question ‘How would you rate the premises you work in and the facilities available?’ The mean average rating for this question was 6.45 in the WSDA, compared to 5.76 in the ESDA, so very similar. Positive responses included reference to the building being well-maintained, having good facilities, being “fit for purpose”, having had recent upgrades (including new internal doors, kitchens, re-painted). The lower scoring responses included narrative which includes reference to; old, tired buildings; a lack of female/dignified facilities; faulty boilers affecting heating/hot water as well as RAAC panelling and consequent issues, including acro-props within the building. In comparison to the ESDA survey results, there is significant reference in WSDA survey results to contamination challenges with properties being a barrier to adequate decontamination being referenced commonly. This level of response may be due to the growing levels of awareness of reported contamination issues affecting the fire sector as a whole. The WSDA survey responses include reference to the word contamination, contaminant or decontamination 210 times (average of 0.35 times per respondent) compared to 60 times in the ESDA survey responses (average of 0.19 times per respondent).

Recommendation 6: We recommend that the Service reviews the WSDA Fire Station condition surveys to understand the areas of most pressure regarding dignified facilities and contaminants to explore any possible interim mitigation measures.

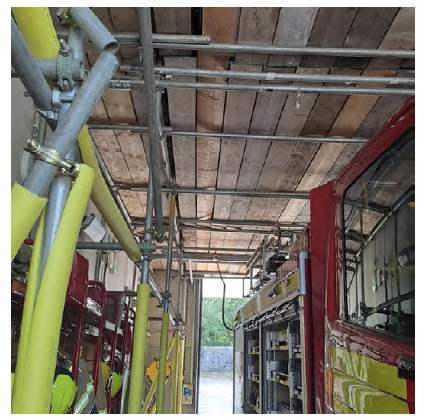

77. Four of the fire stations within the WSDA have roof areas constructed of RAAC, which represents the 2% in Bad condition detailed previously. RAAC was used extensively in the construction of flat roofed public buildings from the 1960s to the 1980s. A safety alert was issued in 2019 following the failure of a roof constructed of this material. The specific stations affected in the WSDA are Stewarton, Cumbernauld, Helensburgh and Milngavie. The SFRS has undertaken a risk assessment and where necessary remedial action to provide temporary structural support for the affected roofs in these workplaces. Prioritisation of which stations will be remediated first is a national strategic decision and is obviously dependent on access to capital funding, which is detailed within its risk based capital investment report. Overall, the situation will have a significant financial impact for the Service, beyond that already spent on temporary support and investigation work.

78. The SAMPP details the projected Capital Programme and it is noted that all four RAAC stations feature in this future planning to a greater or lesser extent. However, it is unclear how long it will take to remedy the defects within the WSDA. As can be seen in the image below the working environment for the staff at some of these stations is less than ideal, and this has been the case for a number of years. Although the SAMPP broadly sets out the Service’s intentions for addressing the defects, it is of concern that this has not progressed significantly since the SFRS Board was first made aware of it in 2019. Staff at those stations reported that it affects their engagement with the Service and community as well as their general morale. These staff should be commended for their ongoing commitment to working in such a challenging environment, for an extended period of time.

Recommendation 7: We recommend that the Service resolves the RAAC roofing problems at the affected stations as a matter of urgency.

79. A number of fire stations in the WSDA have had refurbishment work undertaken to provide enhanced fire safety, windows replaced, doors replaced, more suitable dignified facilities for staff, solar panels installed and improved heating systems etc., which is all to be welcomed. In most case where upgrade work had been carried out staff were very appreciative of the effort although on occasion frustrated by the standard of work completed and the prioritisation. It is understood that the Service has legal duties and responsibility to procurement and contract management, which may restrict practice. That said, some of the staff interviewed reported that they felt the use of the national property maintenance contract and perceived centralisation of decisions and budget control made the process inefficient and ineffective. It is understood that there is a healthy liaison link between Property and the WSDA but the perceived lack of local control and responsibility for LSO management teams was a source of frustration.

Recommendation 8: We recommend that the Service review the existing practices and processes within the WSDA for property maintenance with the Central Property partner in order that increased local administration and responsibility of property be explored.

80. The Service published the Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMPF): Fleet 22-27(4), which sets out how the SFRS aims to design and implement an efficient, reliable, resilient and fit for purpose fleet solution for services across the whole organisation. The Strategy details many identified issues with the Service’s fleet and looks to plan for change. The SFRS’s national Fleet Function manages the procurement and servicing of vehicles used within the area, allocating and replacing vehicles on the basis of a national policy. Some issues identified within the Strategy are the need to improve consultation and engagement, improve the standard of allocated and spare appliances and deliver the West Asset Resource Centre (ARC) development.

81. The appliances allocated to the area are of a varying age and are generally being kept in good condition. Staff were generally content with their appliance and understood the budget constraints the Service has to work within. There were instances where, due to either age or configuration, appliances were in a less than satisfactory condition, but these were limited. Of greater concern to staff was the poor condition of many spare appliances and the lack of equipment provided on them.

82. Major servicing of WSDA appliances is undertaken at the West ARC workshops managed by the central Fleet Function. There is also limited use of local maintenance contracts for particularly remote rural stations. Some staff reported that the use of a predominantly centralised fleet maintenance system and perceived centralisation of decisions and budget control made the process more inefficient and ineffective. Examples of issues included the use of local staff capacity to move appliances to a central point, increased cost of fuel for appliance movements, increased road risk as well as extended periods without vehicles due to logistics and travel. It is understood that there is an established liaison link between Fleet and the WSDA but the lack of local control and responsibility for LSO management teams was a continued source of frustration. Local management teams felt that they had limited influence on prioritising appliance maintenance and replacement and could not escalate or resolve issues effectively.

Recommendation 9: We recommend that the Service review the existing practices and processes within the WSDA for vehicle management with the Central Fleet partner in order that increased local administration and responsibility of vehicles be explored.

83. An issue that was raised with us on several occasions, regarding newer appliances, related to the stowage of BA sets in a transverse locker. The dimension of the locker was said to be too narrow to stow the BA sets without parts of the set catching on the locker door surround, leading to damage of the set or locker edge seal. We are aware that on some of the most recent appliances, there has been a retrofitting of a piece of fabric material designed to hold the BA set away from the locker edges, to avoid damage. However, these ongoing issues seems to have been exacerbated by the addition of Smoke Hoods to BA Sets, which is making the equipment bulkier. We were also informed that the use of the locker at operational incidents could be problematic depending on the road layout and parking configuration, sometimes adding anxiety to an already stressful situation. The health and safety rationale for the locker was well understood by operational staff but nonetheless was universally disliked with other potential solutions frequently offered.

84. We were consistently given feedback regarding specialist appliances. Staff were concerned regarding the age and condition of national resilience assets such as the DIM vehicle and MD units. There was also concern raised regarding the lack of dedicated CSUs and some staff expressed a view that combining with the SORU was not appropriate or fit for purpose. There was also concern raised regarding the HRA Strategy. Staff generally understood the rationalisation process and that the appliances had been removed following an analysis process. However, given that there are now fewer appliances, concern was raised regarding the instances and amount of time the remaining appliances were off the run due to mechanical issues. In some instances, staff gave examples of appliances being unavailable for lengthy periods on end due to delays in processing and getting spare parts. Staff reported that there didn’t appear to be a replacement or resilience strategy for this scenario and that there were often instances of no HRA available within urban areas of risk, for extended periods. The Service accepted that there had been instances of appliances being unavailable but stressed that this had been due in part to supply chain, spare part and training issues.

85. It is understood that there is an established user intelligence group process for appliance development with staff representation and that the SAMPF has looked to improve engagement and consultation. However, staff generally felt that there was still limited consultation or feedback given to end-users of the appliances or equipment when new vehicles are brought into Service. This was also an issue that we raised in our inspection of Fleet and Equipment and continues to be a source of frustration.

86. The Service published the Strategic Asset Management Plan (SAMPE): Equipment 23-28(5), which details how the Service will manage, maintain and develop equipment assets. The Strategy details many identified issues with the Service’s equipment and looks to plan for change. The SFRS’s national Equipment Function manages the procurement and servicing of equipment used within the area, allocating and replacing equipment on the basis of a national policy. Some issues identified within the strategy were the need to improve collaboration, consultation and engagement, improve the standard of allocated equipment and PPE, and to merge stores into the West ARC development.

87. Servicing of WSDA equipment is undertaken at the West ARC workshops managed by the central Equipment Function. Staff reported that the use of a predominantly centralised equipment maintenance system and perceived centralisation of decisions and budget control made the process more inefficient and ineffective. Examples of issues included the limited stock of spare equipment, use of local staff capacity to move equipment to a central point, increased cost of fuel for vehicle movements, increase road risk (MoRR) as well as extended periods without equipment due to logistics and lengthy travel. It is understood that there is an established liaison link between Equipment and the WSDA but the lack of local control and responsibility for LSO management teams was a source of frustration. Local management teams felt that they had limited influence on prioritising equipment procurement, maintenance and replacement and could not escalate or resolve issues effectively.

Recommendation 10: We recommend that the Service reviews the existing practices and processes for equipment provision and maintenance within the WSDA with the Central Equipment partner in order that increased local administration and responsibility of equipment can be realised.

88. Periodic testing of equipment is carried out by fire station personnel as part of their normal routine. These tests form an important part of ensuring that the equipment is safe to use, is functioning correctly, and is ready to be deployed at an incident. The SFRS has no single electronic asset management system for equipment and its testing. The process used in the WSDA is predominantly paper based, we found few issues with the records and equipment was generally well tested and recorded.

Recommendation 11: We recommend that the Service standardise the recording of equipment testing with a national electronic system as soon as possible.

89. There are specialist rescue capabilities, such as water and rope rescue, based at a number of stations within the WSDA. The disposition of these resources is decided nationally and designed to give communities across Scotland equitable access. As detailed previously, some of the capability, such as DIM and MD, was introduced across the UK following the terrorist attacks in the USA in 2001. As with the vehicles mentioned previously, some of the equipment introduced alongside, was said to be at the end of its useful operation due to wear and tear and having had no asset refresh.

90. The BA set used by firefighters, which was first issued by the SFRS in 2016, was described by many of those we interviewed as being overly complex to operate and maintain and prone to defects. We were also made aware of a perceived shortage of spare cylinders in some areas; this was said to impact on training. This was particularly acute in remote areas, as crews were keeping charged cylinders available for operational use because there is limited access to cylinder recharging compressors. In some areas fire appliances are being used to move cylinders and concern was raised regarding the safety, economic and environmental impact of such an approach.

91. The WSDA has a number of Volunteer On-Call stations, some of which are very remote, that are equipped with BA. It is known that BA is a very onerous skill for the organisation to deliver and for individuals to maintain competence, particularly so in volunteer stations where the employment contract is less structured. There are also very strict procedures to allow safe deployment as well as high standards for testing and maintenance. We found that some of these stations were very well staffed and seemed more able to meet these requirements, whilst there were others where it was more challenging. We feel there may be a risk of trying to sustain this skill within some communities, if operational deployment, training and testing standards can’t be sufficiently maintained.

Recommendation 12: We recommend that the Service reviews the existing BA provision within Volunteers Stations to satisfy itself that training, testing and maintenance is being conducted to an acceptable standard and that the capability can be deployed safely within existing policy and operational guidance.

92. A consistent finding in our past inspection reports is the poor opinion that firefighters have of the fire-ground radios and the number of radios available. This continues to be the case. We are aware that the Service is in the process of replacing the current radios with a new digital version. At the time of our fieldwork the project had been running for several years with the roll out of equipment due to be completed by May 2024. However, the ‘go live’ date has yet to be determined.

93. We were advised of the difficulties experienced by some personnel augmenting or changing the standard equipment provided on appliances, even when there was an identified local need. Whilst there are clear benefits in having a standard inventory, we are of the view that as risk is not standard across the country, there will be times when non-standard equipment is required, and local operational needs should be given clear consideration.

94. We were made aware of On-Call appliances, based at WT stations, not receiving equipment on the basis that a WT pump based at the same station has the equipment in question. Staff felt that this situation fails to recognise that the WT appliance may not routinely be available, or may be in attendance at another incident, leaving the On-Call appliance to have to ‘make-up’ for the equipment not carried, such as a Thermal Imaging Camera (TIC), leading to a possible delay.

95. It was also a source of frustration to staff that given the rise in forced entry incidents, bespoke equipment to assist this type of incident such as a power drill, reciprocating saw and door opener hadn’t been provided, after repeated requests. Apart from the equipment mentioned above, personnel were satisfied with some of the level and quality of operational equipment supplied. Appliance Ladders and Powered Rescue Equipment (PRE) were of particular note and received a lot of positive feedback.

96. It was noted that within the D&G LSO area there is SWaH equipment, procedures and training in place that differ from the remainder of the WSDA. Risks locally identified for the area and the Service include varying training standards and equipment, fade of legacy knowledge and skills, maintenance of competency and poor interoperability of crews. These risks have the potential to impact upon crew and public safety as well as compromising the operational response to incidents involving height.

Recommendation 13: We recommend that the WSDA reviews the existing SWaH provision within D&G and develop an improvement plan for consistent maintenance of skills and service delivery.

97. Many of the issues observed in the previous paragraphs were supported by our survey. We asked the question ‘How would you rate the equipment (and if applicable PPE) you are provided with, to carry out your work?’ The mean average rating for this question was 6.98 in the WSDA, compared to 7.27 in the ESDA, so very similar. There is a trend of negative comments regarding BA Sets, highlighting an understanding that BA Sets are becoming defective more often and that they are “old”, at their “end of life”, “10 years old” etc. There are some comments highlighting excessive times taken for workshops to turn around both defective equipment and appliances. There are a number of references highlighting frustrations with the time it appears to be taking to roll out the PRE to replace Hydraulic Rescue Equipment (HRE). There was also reference to requirement for more hand held radios and of a better quality, and there should be a radio for every BA Set.

98. Staff generally provided very good feedback regarding the standard of Structural PPE. In the main, we found this kit to be well maintained and clean, although there were limited instances of soiled gear and poor record keeping. Most staff were extremely aware of contamination issues and from that point of view there would seem to be a positive awareness developing. Disappointingly, nearly all fire stations reported that they felt that the national laundry contract and processes were very frustrating and potentially inhibited a positive contaminants culture. There were numerous instances of staff reporting PPE taking lengthy periods to be returned from cleaning, PPE not being picked up and PPE simply disappearing with no notification as to why. This would seem to have led to a culture where firefighters are reluctant to send PPE away for cleaning more regularly than the minimum. That said, the Service are confident that the standard contract is meeting the agreed triggers for PPE turnaround at the point of arrival for laundry. However, it did highlight issues with the repair contract capacity and process at station as historic challenges.

99. The issues identified with the national laundry contract seem to have been exacerbated by the limitations of spare PPE stock within the Service. We were provided with numerous examples of personnel having difficulty identifying and accessing spare PPE following incidents. These issues were compounded by the perceived lack of a resilient and robust 24/7 process for the National Equipment Function to support operations out of normal office hours. That said, we are aware that at a recent Training Safety and Assurance Board (TSAB) the Service indicated that consideration was being given to additional capital investment with a view to increasing the amount of spare PPE stock. Such an investment could help to alleviate these issues.

Recommendation 14: We recommend that the Service investigate the application of the national laundry contract processes and look to explore improvements within the WSDA.

100. A frequent comment made by crews was that the Structural PPE provided was good, but not the most suitable for use at Wildfire incidents. Structural PPE can cause the wearer to overheat and the footwear can be uncomfortable when walking for long periods over rough terrain. As such, it is generally recognised that lighter weight wildfire PPE is more appropriate for these types of incidents. It is understood that the Service has a Wildfire Strategy, and that lightweight PPE is being distributed to those stations designated as Wildfire Stations. We were made aware of numerous examples of non-wildfire stations attending wildfire incidents regularly and for long periods of time, which is consistent with commentary made within the HMFSI thematic inspection (Climate Change: managing the operational impact on fires and other weather- related emergencies 2023(6)). Some firefighters talked about their feet being “shredded” during the peak of wildfire season and buying their own blister plasters and medication to help get through the worst, which is clearly not an ideal situation.

101. An element of staff reported that they were unhappy with the quality of the non-operational uniform at the moment and that there was a feeling that the standard had reduced considerably year on year. Examples included, reduced quality of material, need for more regular replacement, inconsistent sizing, poor fitting and not being fit for purpose. There was a sense that the uniform was important and helped them connect with the Service, with a sense of pride. A number of those we interviewed felt that the uniform was being bought on a predominantly cost basis and consideration as to identity, functionality and quality was very much secondary. The Service’s financial position was understood but many firefighters thought that the balance of considerations wasn’t good. It was disappointing to observe the impact of this feeling on staff engagement and morale.

102. Many of the issues observed in the previous paragraphs were supported by our Survey. As detailed previously, we asked the question ‘How would you rate the equipment (and if applicable PPE) you are provided with, to carry out your work?’. The mean average rating for this question was 6.98 in the WSDA, compared to 7.27 in the ESDA, so very similar. Generally, the comments were positive around the quality of structural PPE. Although there was reference to two sets of fire kit not being enough for crews, along with delays in getting spare kit and laundry turnaround times, which linked to decontamination issues highlighted in previous paragraphs. There were also mention of limitations of structural fire kit and this not being suitable for wildfires. Lastly staff mentioned the uniform and reference to it being a poor quality.

103. The Service should routinely train and exercise internally and with multi-agency partners externally. Although too numerous to mention the WSDA has a number of significant hazards and risks that meet the criteria of Nuclear and Control of Major Accident Hazards (COMAH) establishments, which require site operators to test emergency plans. Also, within the WSDA there are hazards associated with sub-surface transport, places of incarceration, places of care, transport infrastructure as well as major industrial, residential and commercial premises, which could all require scheduled exercising. It is understood that the impact and response to the COVID pandemic did have a negative effect on the ability to train and exercise. However with the removal of restrictions it is believed this activity is returning to normality. We found strong evidence that the Service is taking part in joint exercising and on many occasions, the Service within the WSDA was leading the partnership approach on behalf of the LA. The Service within the WSDA has a very positive reputation in this respect and is a trusted and active partner.

104. In respect to internal exercising, we found some evidence of Station personnel developing and conducting exercises offsite. Where these exercises had been delivered, they were well received by station personnel who seemed enthused by the innovative and diverse training. Staff reported that some limitations to this local offsite exercising were in part due to the lack of confidence to complete the planning, risk assessment and authorisation processes. It is unclear whether this is from lack of development and/or the perceived bureaucracy involved. The Service reported that all LSO areas are exercising on a regular basis but are aware of the reluctance of some staff to develop their own.

105. We found evidence of an LSO area developing a two-year training and exercising programme. The document schedules 12 three pump exercises per year and all stations in the area are involved with development and participation. There was evidence that the planner was in use and also evidence of the area conducting a large six pump exercise at a local hospital. It is understood that this programme is being assessed by the other WSDA LSO areas with a view to adoption in some way. We found the planner to be a very positive addition to operational preparedness.

Good Practice 5: We were very pleased to observe the development of a comprehensive exercise and planning schedule within one LSO area. We believe that this is a good development and the Service should consider that all areas in the WSDA adopt the practice.

106. Some fire stations within the WSDA also respond to incidents over the border in England and vice versa and there are arrangements in place for the exchange of relevant information when working together with Cumbria Fire and Rescue Service. The working arrangements were said to work well.

107. There is an Operations Control (OC) based in JOC, one of three covering Scotland. JOC is responsible for handling emergency calls in the WSDA. Although JOC will handle the majority of the calls for the area it is also possible for the other two OCs to handle WSDA calls for resilience purposes. Although based within the WSDA the DACO has no direct control over the OC management, as it forms part of the Operations Function within the Service’s management structure. However, there is an expectation that both the WSDA and JOC work together to ensure efficient and effective operational response.

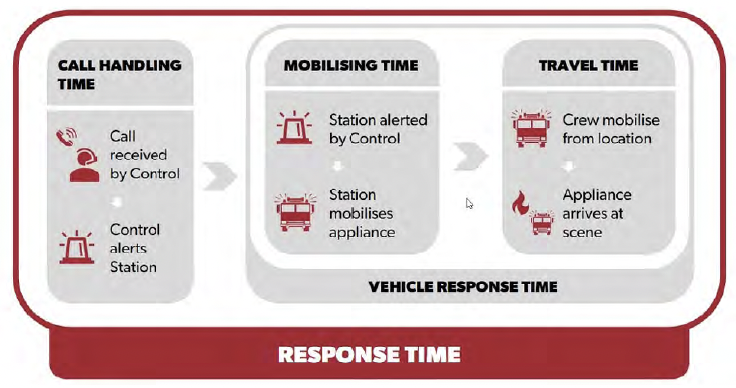

108. As per Figure 2, call handling time is the cumulative time for JOC receiving a 999 call and then alerting the station or vehicle. Whilst response time is the accumulation of call handling by JOC plus mobilising and travel time of the vehicle or resource, call handling and response times are reported nationally. As of the reporting year 2022-23 the median time for the JOC was 1m 15s which is slightly lower than the Scottish and ESDA median, which are both 1m 19s. There have been no national standards by which to measure speed and weight of response since the removal of the standards of fire cover in 2005. However, the median response time to attend an incident within the WSDA is 8m 5s, which is slightly lower than the Scottish median at 8m 44s and significantly lower than the ESDA median at 9m 20s. There are many factors that can contribute to these figures, so it is very difficult to compare like for like and to a standard. On the basis of these figures alone we see no cause for concern with JOC compared to the rest of Scotland.

Figure 2 - Response Time diagram

109. The OC is one of the most important parts of the Service’s operational response as it receives 999 calls as well as despatching and managing the appropriate resources to respond. OCs are currently managed in a functional structure with no dedicated middle manager having overall responsibility for JOC. JOC Watches are expected to liaise and communicate with the appropriate OC middle manager depending on their area of functional responsibility. We found many JOC staff frustrated by this structure as there was no single point or clear route by which they could progress issues. It is understood that there is currently a review of the Structure ongoing, which may initiate change and we look forward to monitoring the progress and outcome of this review.

Recommendation 15: We recommend that the Service completes its review of the Functional Management structure within JOC to ensure staff are being supported and operational preparedness is being delivered in the most efficient and effective way.

110. To ensure the best results, the operational relationship between JOC and the WSDA should be strong and effective. JOC staff were able to provide evidence of occasional Flexi Duty Officer (FDO) engagement sessions and having positive relationships with ‘go to’ station personnel for help and advice. However, we could not find strong evidence of JOC staff routinely playing an active part in LSO management meetings or having a significant role in the performance of the Area. Although based within and serving the WSDA, there didn’t appear to be very strong operational management or operational preparedness links to the SDA LSO teams.

Recommendation 16: We recommend that the WSDA should seek to strengthen and improve the operational and managerial links to JOC to improve operational preparedness and delivery.

111. We also found some staff within JOC extremely frustrated and concerned about the introduction and go live processes of revised or new policy and procedure. The staff recounted numerous examples of difficulties with system configuration and preparation, poor planning, limited training, poor problem resolution, limited consultation and limited engagement. The introduction of the UFAS policy, the SSRP appliance removal, HRA Strategy changes and the reinvigoration of the Strategic Cover General Information Note (GIN) were cited as prime examples. JOC staff believe that these issues have exacerbated staff turnover, absence rates for OC staff, workplace anxiety and resulted in poorer organisational performance.

Recommendation 17: We recommend that the Service should review its consultation and liaison process to ensure that the staff at JOC are provided with enough ‘lead’ time to prepare and train for policy and procedural changes.

112. The Service implemented a series of initiatives and changes during our fieldwork and we feel it is incumbent on us to detail our observations. As detailed in the introduction to this report, the Service; introduced a new UFAS policy in July 2023, which altered call handling and mobilisation processes; instigated a temporary Appliance Withdrawal Strategy in September 2023, which removed five pumping appliances (three from City of Glasgow, one from South Lanarkshire and one from Inverclyde) from the WSDA as part of the SSRP. In addition, it also implemented a HRA Strategy in September 2023 which removed seven height appliances from the WSDA with a net reduction of fifteen down to eight and implemented the standardisation of water rescue provision on the River Clyde in September 2023, which altered crewing for water rescue at Polmadie Fire Station from a dedicated to a dual staffing model.

113. In the main, the UFAS policy has been well received and staff are engaged with and understand the rationale and benefits. At the time of our fieldwork, the use of the additional capacity to the Service had not been fully realised. As such, it was difficult to gauge the impact on performance. Two notable issues are that JOC feel they are not realising a significant positive effect on their capacity, as they are dealing with the same call numbers as well as the increased call challenge aspect. However, the Service feel that whilst the call challenge might take slightly longer, if this results in a non attendance, the incident workload attached with the management of an incident should be reduced, which may start to realise more capacity for JOC. In addition, some On-Call staff expressed concerns regarding the balance of income, which has dropped, versus the commitment of hours to the role. There were instances of staff seriously considering their tenure within the Service due to this issue. We are aware that the WSDA had offered additional engagement work to utilise the extra capacity, but the up take was limited as staff seemed reluctant to commit to non-operational work away from their primary employment. We note that UFAS performance is reported on a quarterly basis to the Service Delivery Board, then Service Delivery Committee and that any concerns identified should be managed at these fora.

114. The introduction of the other three strategies in September 2023 had significant impact on the WSDA, which was picked up latterly in our fieldwork. It is understood that there was a need for confidentiality regarding the proposed changes, that could be construed as being sensitive. Staff and partners were also somewhat sympathetic to the financial position of the Service and empathised with the need to change. Indeed, it is recognised that the Service also engaged with the HMFSI regarding this proposal who provided feedback on the data analysis at that time. However, many staff as well as internal and external partners reported that they felt the speed of the announcement was not appropriate, and that transparency, engagement, communication and consultation was very poor. They were critical of the analysis outputs and the prior communication from the management teams, LSO and Senior Leadership Team (SLT), which has led to a sense of mistrust of senior management. Consequent engagement has gone someway to repairing this loss of trust but, in some respects, it has only reinforced it. Staff at all levels reported emotions and criticism routinely linked with the challenges of change process.

Recommendation 18: We recommend that the Service should review its consultation, communication and liaison process to ensure the staff and partners are fully engaged in future substantial change processes.

115. It is still early in the change process and it appears the Service in the affected parts of the WSDA is still forming and adjusting to the new norm. Staff appreciate that changes are needed and even accept that further change is inevitable. However, there is a level of anxiety around this with some staff reporting that they feel less secure in their post. They also report that all the effort and capacity seemed to have gone into implementing the changes with little cognisance taken of reviewing existing targets, workload and process, whether they be nationally derived or local. Operationally, staff report that they feel the WSDA is less resilient, they often feel exposed at incidents, they feel less safe at work, and they feel that operations are less effective. Whether this is the reality is currently unknown and concerns should be picked up by the operational assurance process in time. It is however the perception of many staff at the moment. We accept that the Service has only recently delivered these interim changes to operational capacity and that this change process is ongoing, with a formal consultation process scheduled. That said, we feel that there is a need to fully understand the effect on appliance movements as well as consequential capacity and workload changes within stations.

116. A positive aspect reported regarding the changes, was the staff management and movement process. Staff reported that this was handled well by the LSO management teams in the WSDA, with peoples’ personal circumstances and welfare heavily influencing transfers. The WSDA received no grievances throughout the process. Transfers weighted on personal need as opposed to operational need has inevitably resulted in increased DD of drivers and those personnel with specialist training.

Good Practice 6: We were very pleased to observe that the staff movement process within the WSDA was very successful and was applied with no recourse to grievance. We believe it would be worth debriefing this process in the WSDA to capture learning for any future modernisation issues that require staff movement.